Somehow, some people are often asked to mediate in disputes among others. The author has been in such a position a couple of times but not enough to write a book on the subject. Still a quick checklist to avoid some common pitfalls I find helpful for myself – and maybe others would be interested as well.

What is mediation?

Mediation for me is a voluntary process of resolving disputes or, the art of helping two parties to agree sufficiently on a subject so that both may interact mutually advantageously in the future. That dispute might be on a difference in interests, but also a difference of truth/conviction/vision, or a difference of observations of the same objective facts. The main impediment to discuss their differences in interests generally are emotions that ran up so high they are blocking progress on the road forward. The mediation of these emotions often is the essence of ‘mediation’ as a whole.

The depth of the emotions often is reflected in the intensity of mediation required to reach results:

- After separate discussions with a mediator, both parties resolve their issue amongst themselves

- The presence of a mediator is required during the resolution, whereby the length of the process and the time invested provide an indication of the intensity.

- Also with a mediator present resolution remains out of reach, and the mediators conclude they are unsuccessful. An escalation to another form of resolution might ensue (be it legal proceedings or in bigger conflicts even war etc.)

Which are the requirements for mediation to succeed?:

- First of all, there needs to be a – preferably emotional – tie between the parties, some overarching interest that is the ‘why’ for mediation. Membership of a group of friends, employment in an institution or professional association for example.

- Second, both parties need to accept a third party to intervene, so this third party needs to be acceptable to all parties involved. In practice, this means to have at least a reputation of integrity and impartiality.

- Third, this third party needs to be both willing and professionally/personally equipped. How to determine this requirement is difficult, but please ensure all agree explicitly that this ‘proper equipment’ is so. And if any one involved party does not think that is the case, that is the case.

- Fourth, there must be a possibility to have one-on-one conversations, to slowly ‘peel off’ the situation step by step without being sidelined by group complexities.

If the considerations above are not fulfilled, it is better not to think about mediation at all: let then the embroiled parties fight it out, do not get yourself entangled into a mission impossible. Sometimes the pain needs to increase before the patient accepts a medicine.

Then, the resulting process should take the following steps. Each of these steps can be framed in such a way that it facilitates progress to the next step towards a successful resolution of the differences, whereby an agreement to disagree could be a perfectly reasonable outcome. But preferable without the loaded emotions that would preclude future interactions, without the polarization.

Phase 1: Core Process steps

First, only the mainly and directly involved parties need to resolve their differences

- Both quibbling parties need to express a willingness to resolve their differences. A professional code that they need to be open to or even be able to do so themselves creates a ‘need to act’ for them to maintain their group membership.

- Then both need to accept the mediating party. An accepted mediator in the group greatly facilitates this step. If there are two mediators involved a chance of a ‘drama triangle’ from Transactional Analysis is greatly decreased.

- By inquiring into the specific nature of the grievances, the mediator forces the quarrelers to consider the ‘marketability’ of their concerns, and a lot of ‘air’ that can build up due to non-communication is likely to evaporate. During non-communication emotions are ‘built-up’ to support the claim of pain, whereas the mere expectation of communication to the public generally brings back some more realism to the choice of words.

- Often it makes sense to then ask parties to write down their timeline of observations, or the ‘facts’ they use for their judgements and emotions. Often, simple misunderstandings turn out to be the basis of much mischief. The downside is that this step is unusual, time-consuming and might not have much acceptance with emotionally tied participants. However, if one is not willing to explain one’s truth, then how interested is one in really resolving a conflict?

- Crucial in this stage is that actual conversations are one-on-one to keep them pure. A grieved party should only talk about what happened to him or her personally. Replacement emotions “he did this to Ben, which is not acceptable to me” do not belong here (yet) but in Phase 2. It is remarkable how many people are emotionally upset about something that has happened to a third party who does not even think twice about it. (Or behind which ‘big back’ one can shield his own emotions.)

- The consideration of a potential intervention of the mediating party in a way establishes that the parties are not capable of professional behavior. This ‘threat’ or in some cases ‘ loss of face’ facilitates a playing down of the effect so that ‘I am not difficult at all’. If the clarification of the outside view by the mediator allows to do so, a direct one-on-one resolution conversation allows face- and time-saving for all involved., although one runs the risk of the conflict not being resolved and the bushfire to continue unchecked.

Phase 2: Separate Bystander effects

Where John is insulted how Ben is being treated, John is only a bystander.

- If one finds out that in the relationship between two parties a ‘bystander effect’ is involved, ideally first the matter is resolved with the directly involved party only. Give everybody the dignity to speak for themselves. And the emotion of the directly involved usually acts as a ceiling for the emotional involvement of bystanders.

- In case a group is affected, the insulted/affected party should focus on what kind of effect the behavior has on her (regardless whether she is part of the group or not). Nobody but their elected officials should have the arrogance of speaking for a whole group.

Phase 3: Resolution: what is included and what not?

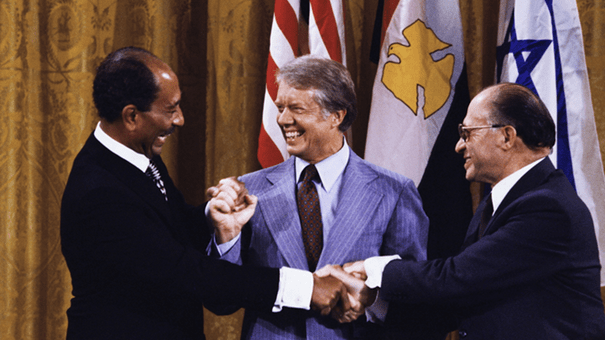

Crucial here for conflict closure is that both parties involved need to make a public gesture of resolution: like Begin and Sadat shaking hands under the watchful eyes of Carter sealing the Camp David Accords. In our lives the topics to mediate probably will be less impactful, but the process remains identical.

Elsewhere, I have made a distinction of all statements into Information (‘facts or observations’), Analysis/Decision (‘feelings and interpretations’) and resulting Actions. Only after the emotions of Phase 1 and 2 have been completed is it time to look at the consequences one can draw out of the situation. One can emotionally positively (or maybe neutrally) approach an individual but still do not consider her fit for a particular position. The mere fact that ‘two people have had a good heart-to-heart conversation’ does not mean they are best friends: we might be ok to play in the same team, but I do not want you as my roommate in the next soccer camp. We might even be best friends, but I still do not think you are fit for the chairperson position.

Conclusion

A simple checklist is nice, in practice situations usually are more complex. Add that also mediators are prone to make mistakes, and these kind of trajectories have a significant chance of running amok. Also, and especially, at the risk of the mediator. However, the bounty at the end of the horizon is removing emotional barriers that can eat up the happiness of people we consider dear. This author remains confident that the words above might add to the quality of mediation and wishes a lot of wisdom to all who venture on this path.